The Two-Parent Diversion

Why focusing on family structure is not a promising way to help more kids thrive.

Economist Melissa Kearney has written a high-profile and compassionate book to galvanize action around the decline of two-parent families. I love Kearney’s research on the origins of single parenthood and inequality. But I’m of two minds about her book.

On one hand, I love that her policy recommendations reflect her deep appreciation for the structural roots of declining marriage. She’s not insisting that individuals just make different choices. She shows how changes in labor markets – due to trends in technology, trade, unionization, minimum wages, and mass incarceration – have all made it harder for less-educated workers to support a family. Then she tries to address these underlying constraints on people’s individual choices.

And to that end, the book suggests massive new public investments in skill development (child care and pre-K, K12 schools, after-school and summer enrichment, community college and early career support), alongside expanded wage subsidies for low-income workers, and more experimental efforts to increase co-parenting and supportive fatherhood. Maybe the focus on two-parent families can bring a different audience on board for these policies. If more social conservatives came to support expanded wage subsidies for single workers – not because they thought single workers warranted support, but because supporting them might increase marriage rates – that seems good.

I also appreciate how Kearney, like many others including sociologists Annette Lareau and Douglas Downey, insists that we can’t address growing inequality without understanding the huge role of family environment in driving unequal child outcomes. A lot of people today interpret statements about family inequality as coded statements about family superiority/inferiority, or coded expectations that families should solve these problems on their own. Kearney helps to refute these assumptions.

On the other hand, I find the book overstates the importance of two-parent households based on existing evidence, undersells the potential benefits of its own policy recommendations and pro-kid policies more generally, and doesn’t make it clear that enacting such policies will require New Deal levels of investment, i.e. hundreds of billions of dollars per year.

This combination tends to reinforce a false yet popular idea that changes in private family behaviors and relationships – without major new public investments – can go a long way toward closing rich-poor opportunity gaps for kids, AND that public efforts will somehow be futile until these private arrangements change. I sensed such sentiments in warm reviews of the book by people who probably do not support anything like the book’s actual policy recommendations (e.g. here, here, here).

So in this post I won’t argue against Kearney’s main policy recommendations, which I like and which I think would help a lot of families raise happier, higher-skilled kids.

Instead, I’ll argue against a view — which I predict Kearney’s book will be cited to support for many years — that focusing directly on marriage and family structure is a good way to help kids. I’ll show that:

Direct efforts to increase two-parent families have never worked.

Even if we find programs that work, no one will use them.

Even if programs did work and people used them, it wouldn’t matter.

Fixating on marriage fosters public policy defeatism.

Direct efforts to increase two-parent families have never worked

Many standard policies designed to improve outcomes for less-advantaged families are likely to increase marriage and two-parent families indirectly. I say “indirectly” because that has never been the main goal of these programs; it’s been more of a side effect.

These policies affect marriage indirectly by expanding the pool of men and women with ample capacity to support others rather than scraping by on their own. Some of these policies target adults (wage subsidies, job training, criminal justice reform), while others target kids with an eye toward improving their future outcomes in adulthood (early education, tutoring, college, apprenticeships).

Then there are policies that try to affect marriage and co-parenthood directly. These kinds of efforts include marriage and co-parent counseling, fatherhood counseling, reductions in “marriage penalties” embedded in safety net programs, public service announcement-style advertising campaigns, and efforts to change social norms such as asking people to be, as Kearney puts it, “honest about the benefits that a two-parent family home confers to children.”

These direct efforts all have something in common: they ask almost nothing of taxpayers. And unfortunately, as Kearney documents, convincing research finds these programs have never worked. They have struggled to change parental behaviors at all, much less yield substantial benefits for kids.

That might suggest the only viable option is to go the indirect route: improve people’s economic fortunes, and hope that changes their family-formation behavior. But Kearney argues that won’t work either, for an interesting reason.

In her research with economist Riley Wilson, she finds that a recent burst of good working-class jobs related to the fracking boom didn’t increase marriage as much as a similar burst 50 years ago related to the coal boom – even though both episodes led to an increase in births. She concludes that men used to feel more obligation to support their children, and until we bring back that kind social and moral pressure, just expanding economic opportunity by itself may fail to restore two-parent households.

I don’t find this argument convincing. Resource booms are weird shocks. They bring in a lot of migrant workers who lack any roots in the local community, and who also disproportionately lack strong attachments to their home communities. The fracking boom didn’t increase marriage – but it did increase violence. Yet no one worries that broader economic opportunity would increase violence. This suggests the fracking boom isn’t a great microcosm for studying these issues.

There is one slightly more promising direct approach: TV. The hit reality TV show 16 and Pregnant (may have) reduced teen pregnancy, and Brazilian soap operas increased divorce and reduced fertility. So it’s worth thinking about how mass media messaging can benefit society in co-parenting and many other domains. But the idea that asking Hollywood to emphasize more two-parent norms can significantly narrow childhood opportunity gaps seems … questionable.

For her part, Kearney thinks we have to keep searching for direct ways to increase two-parent family formation, because it’s so important, and because she’s convinced by her fracking case study that we can’t rely on economic empowerment alone.

Which leads to the next problem.

Even if we find programs that work, no one will use them

Based on the failure of marriage programs, Kearney advocates more investment in programs that support co-parenting and engaged fatherhood.

This gets into the wide world of parent training programs. The key thing to know about these programs is that they have never caught on among parents, especially among the less-educated, lower-income parents whose behavior Kearney is most eager to influence.

Why is that? While doing research for my book, I attended a parent training program myself to see what it felt like. I chose a reputable program that many parents had to attend to comply with court orders, because I wanted to see how these classes would feel when they weren’t just serving the college-educated go-getters who tend to participate voluntarily. I went for 2-3 hours every Thursday after my full-time job for three months.

Here’s how it felt: informative, awkward, and exhausting. I definitely would have stopped attending if I hadn’t felt a researcher’s compulsion to experience the whole thing before writing about it.

My experience, and the research base on parent training, made it clear to me why these programs have not caught on, and why the parents who are most in need of these programs are the least likely to participate in them.

Less-educated, unwed parents have (on average) had disproportionately crappy experiences with schools, classes, counselors, and authority figures in their own lives. They also have less stable jobs, addresses, child care, transportation, health and health care, appliances, and relationships. And at least in the case of single moms, they are typically very busy. Under these circumstances, it’s not hard to see why they might decline to attend that optional “Healthy Co-Parenting” program after (during?) work on Tuesday nights, even if tenured professors and philanthropists think it might be good for them.

Even amazing programs such as the Nurse Family Partnership, which sends registered nurses to visit low-income, first-time moms at home to help them get oriented with healthy child development practices – even these effective programs struggle to recruit and retain participants. As one mother put it, “I was doing so much. I was going to school, trying to work. I couldn’t keep appointments. … And I was a new mom, first time mom. It was just too much.” The Nurse Family Partnership has demonstrated positive impacts that marriage counseling and fatherhood counseling programs can’t yet even begin to dream about.

The problem here is simple. Asking more of individual working parents – more time, more energy, more money – is not a promising approach to reshaping the opportunity landscape for kids.

That is why we should be nudging the policy discussion toward ways we can ask less of parents, and more of professionals such as teachers, tutors, and counselors by expanding public support for automatic, hassle-free child development opportunities way beyond the confines of our existing K12 education system.

Even if programs did work and people used them, it wouldn’t matter

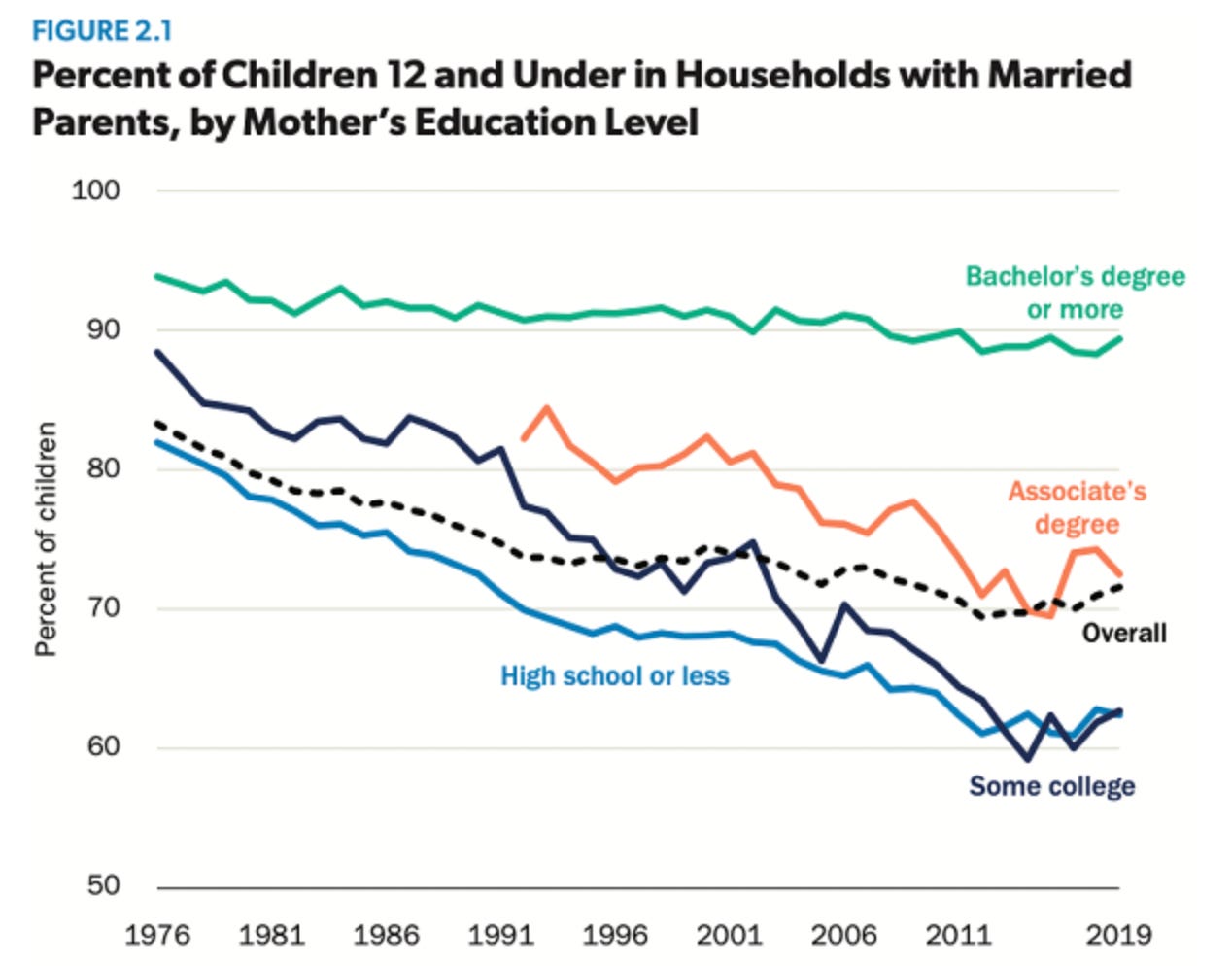

If you look at correlations, two-parent families seem very important for kids.

Consider one key child outcome: college graduation. Among mothers with high school degrees but no college, two-parent families are associated with a 13 percentage point increase in kids’ college graduation rates. That’s big! But even if all these mothers got married, the correlations suggest we’d still see a 39 percentage point gap between kids born to married mothers with high school vs. college degrees. So yes, correlations suggest marriage may be important. Not nearly sufficient to address most class-based differences in long-term child outcomes, but important.

And it only gets worse from there, because causal effects of two-parent families on kids – to the limited extent researchers have been able to measure them well – are much smaller than correlations suggest. This means getting more folks coupled up, without addressing the other deep constraints that led them not to couple up in the first place, will yield far smaller benefits than we’d expect based on correlations.

Why is that? Getting married is a sign that people have their lives in decent shape more generally: stable careers, a leash on mental health problems, a clean criminal record, a supportive extended family, and so on. The research on causal impacts tells us that these background factors, rather than the presence of a second parent per se, drive a lot of the positive associations between two-parent households and good child outcomes.

The way Kearney and many others elide this fact is by switching focus from the magnitude of impacts, to the existence of any impacts at all. “[The] thing staring at us from the data is overwhelming,” writes Kearney. “‘[H]aving a second parent in the home … is, on average, beneficial for children’s outcomes.” She’s right! It’s just that these impacts are far smaller than pro-marriage advocates wish they were.

To see the implications, suppose we invent a new program that increases the share of low-income kids raised by two involved parents by 10 percentage points. This is enormous, and light years beyond the capacity of any program ever devised so far – but let’s roll with it.

The best evidence suggests this would likely have no impact on kids’ academic achievement, no impact on college graduation, and might increase the educational attainment of all poor kids on average by something like 0.02 years or even less. The rich-poor gap in years of schooling for kids is around 2.5 years. So this miraculous new hypothetical pro-marriage program just reduced the rich-poor gap in educational attainment by less than 1%. The best estimates would predict similarly positive, but small, impacts on kids’ mental health and social-emotional outcomes. Not too promising.

Kearney never says outright that causal impacts of marriage are huge. But to the extent her language and emphasis kind of suggest it, readers may wind up confused. For illustration, here are conclusions from two empirical papers by well-known researchers in the literature:

Policies seeking to change the living arrangements of low-income children may do little to improve child well-being. – Foster & Kalil (2007)

[Our results] suggest that residence in single-mother … families, as well as transitions to single-mother families, are associated with relatively small increases in children’s behavior problems and, to a lesser extent, declines in achievement. – Magnuson & Berger (2009)

Compare that to direct investments in kids such as high-quality child care, tutoring, college support, and so on, which I advocate for under the pitchy label of “Familycare,” inspired by Medicare. Research on causal impacts of these programs, and from adoption studies that make similarly major changes in childhood environments, suggest that Familycare would close most of the large rich-poor gaps in education and career outcomes. Here is a quote from one paper summarizing likely impacts of universal high-quality child care from ages 0-3, based on results from the almost absurdly rigorous Infant Health and Development Program:

[Such] a program offered to low-income children would essentially eliminate the income-based gap [in cognitive skills] at age three and between a third and three-quarters of the age five and age eight gaps. – Duncan and Sojourner 2013

So it’s really night and day in terms of two-parent families vs direct investment in kids. Which leads to the next problem.

Fixating on marriage fosters public policy defeatism

Because Kearney suggests we have to address one particular aspect of inequality that is very hard to change directly, she falls into a kind of murky, unconvincing optimism. “No single program,” she writes, “however effective, will level the playing field, but moving the needle in a hundred little ways can add up.” What hundred little ways? Add up to what?

She highlights misleading research claiming that Denmark, with all its ambitious child development policies, has almost identical rich-poor child outcome gaps as the U.S., implying we have to set very low expectations on what we can hope to achieve with better pro-kid policy. You can check out my longer Twitter thread to see the many reasons why I find this misleading. One key point is that Denmark’s pro-kid policies do appear successful, but the positive impacts on kids get a little stifled for interesting reasons by Denmark’s radically more generous safety net for adults. Denmark does not prove any simple point about the futility of pro-kid public policy and I’ll write more on this in a future post.

The downside here is that Kearney’s book will strike many as reason to surrender hope that public policy can make a dent in social class, even if Kearney herself (sort of) states otherwise.

Which is why I think it’s better to focus everyone’s extremely limited attention on building skills in kids, rather than trying to make their parents do hard, specific things they may be unable or unwilling to do for deep reasons. Familycare, like its namesake Medicare, would cost hundreds of billions of dollars per year (though a lot less than Medicare, and about the same as Kearney’s overall policy proposal if you take it literally). And it would level the playing field in exactly the way Kearney’s readers may learn to assume we can’t achieve.

Look at it another way. Medicare and Social Security have had a huge equalizing impact on old age in ways that no amount of private support from family members ever could have achieved. Now, someone might point out that married couples have an easier time taking care of their aging parents, just like they have an easier time taking care of kids. Married couples also have an easier time taking care of themselves in old age. But no one today would argue we can’t solve the problems of the elderly without increasing marriage rates. In Medicare and Social Security we have chosen to transform old age for the better, and we could do the same thing for childhood. It just requires public investment.

But aren’t dads super important?

None of this is to insist on a zany idea that parents – both moms and dads – don’t matter. I think parents matter enormously! It’s just that parents matter in far more sprawling ways than their marital or co-parenting status.

Of course, like anyone else with a beating heart, I wish all kids could have two supportive parents. I also wish people weren’t ever jerks to each other. I wish Haagen-Dazs Vanilla Swiss Almond ice cream were healthy (maybe??) and rainbows adorned every sunset. Alas, as of now, we don’t have good public policies available to achieve these things.

And fortunately, we don’t have to. If we enact certain large new public investments in child development, millions of kids who grow up with single moms may still wish they could have had two supportive parents. They might feel pain and wonder why their fathers chose not to support them more actively. But they will do better in school, be mentally and physically healthier, get good college degrees or vocational training, build more lucrative and fulfilling careers – and yes, they will also wind up more likely to get married and raise kids in their own stable, two-parent households.

For her part, Kearney does advocate for big pro-kid investments, even if she doesn’t explain the costs and severely understates the benefits. So I hope her book expands the coalition of folks willing to support these policies, rather than confusing people into a false belief that major progress remains out of reach until we get more parents to marry.

I began reading this convinced I would disagree with Mr. Hilger, but by the time I'd finished, he'd persuaded me. Two parents are clearly better than one, but in a sense the two-parent household is a halo effect from a constellation of other positive conditions, the most important of which is an income adequate to survive in our society and the education and skills to earn such an income.

Great article.