A few months ago I had the honor of speaking at the National Social Mobility Symposium at Cal State University San Marcos. CSU San Marcos is one of the best colleges in the country in terms of catalyzing upward social mobility and it was a joy to be there and feel pride in my state and country for creating these kinds of institutions.

My job as a speaker was to lay out the economic case for college. In preparing the talk, I noticed an upsurge in provocative, data-driven claims that college isn’t that great a deal after all. I felt these claims were misleading, but I knew a lot of parents and policymakers might struggle to reconcile them with the usual notion that college made all the sense in the world.

So I’m continuing my “What Individual Parents Can Do” series (see previous installments on tutoring, sugar, and extracurricular activities) with a 2-part post on college. This first post will clarify why college remains a great investment — an anti-backlash defense of conventional wisdom. Part 2 will explain why college is also a key juncture where individual parents can benefit their kids, keeping in mind the only way to expand college access at scale will be to make it simpler and cheaper.

College done well is a great investment

One of the best things individual parents can do for their kids is usher them into good colleges and good majors.

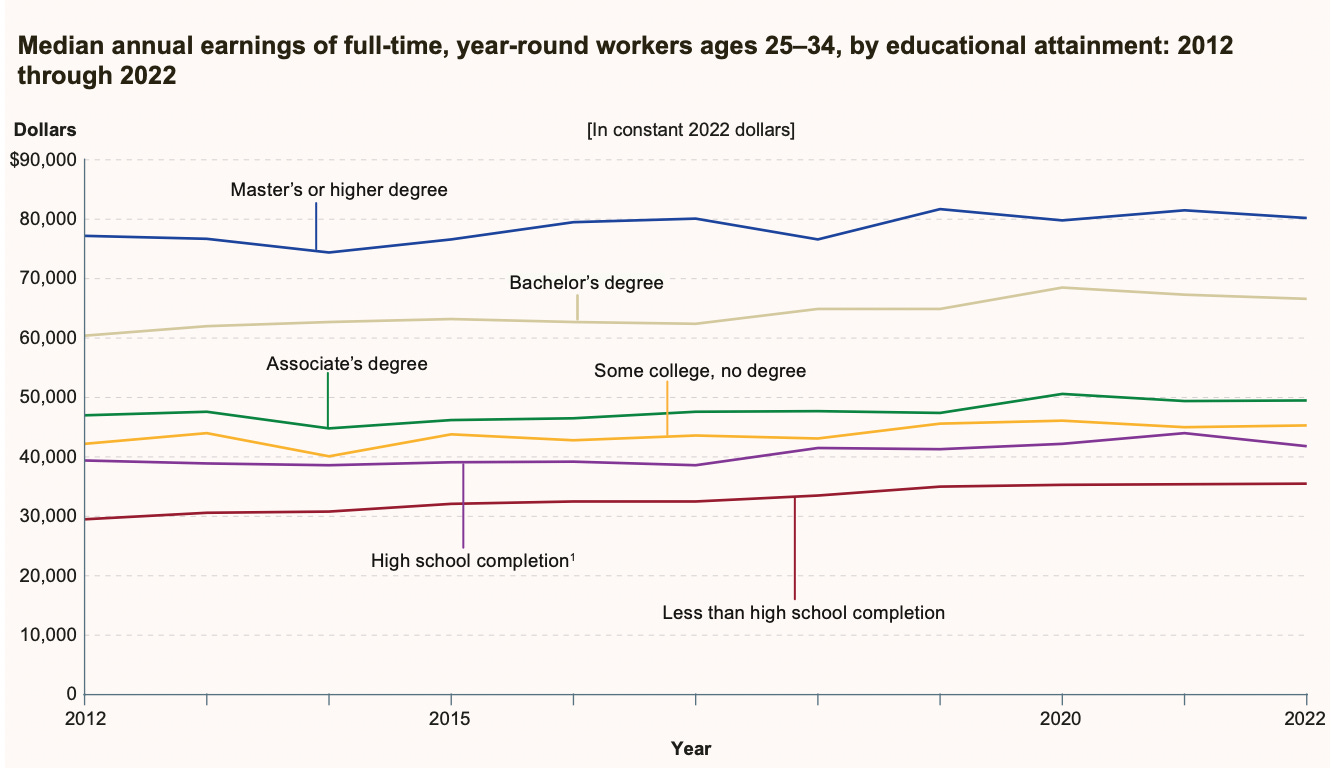

College is not just a financial investment, but on average it pays off extremely well in dollar terms. It costs about $100,000 in tuition and (mostly) foregone earnings over 4 years, but graduates tend to earn around $35,000 or 88% more per year than high school graduates for the next 40 or so years of their working lives — $75,000 vs $40,000 per year. These numbers imply college has a rate of return that beats all other conventional financial investments. It’s the normal person’s chance to invest like Warren Buffett. I don’t like the financial aid reductions proposed by Congress, but they won’t dent these calculations.

If the financial rewards alone don’t float your boat, college graduates also enjoy more fulfilling, flexible, and secure jobs, innovate more, take better care of their own health, maintain better relationships, and feel happier—even compared to people who have similar incomes but didn’t graduate from college. Because parenting involves a lot of general skills, college helps people raise healthier, higher-skilled, and more innovative kids. In other words, getting your kids into good colleges will benefit your grandkids. College might even help your kids take better care of you when you get older. If you value anything, there’s a good chance college gets you more of it.

I also think people underestimate another value of college – it compels a large early life investment. Investing is hard. Our default is to spend on things we want today, not invest to get more of what we want tomorrow. To attend college full-time, kids typically forego full-time jobs, which amounts to investing into their education the entire salary they would have earned over multiple years alongside additional funds from parents and lenders. So college inspires families to make big, irreversible, long-term investments with resources they otherwise would have mostly spent rather than saved. That would be valuable even if the benefits of college were smaller than they are today.

As an aside, the impacts on earnings imply that colleges are local economic treasures. Imagine a set of businesses that had multi-billion dollar valuations, but no billionaires – because they distributed their profits in multi-hundred-thousand-dollar slices to their customers instead of founders and early investors. CSU San Marcos, for example, is a 4-year public university attended by 17,000 students per year. If you compare its expenditures to the lifetime earnings gains accruing to its students, a for-profit business with similar numbers would be valued at north of $5 billion. That kind of valuation would put CSU San Marcos in the top tier of US publicly traded companies.1

Why are some people skeptical?

I suspect one reason many people are skeptical of college is that the basic math can appear so favorable it feels too good to be true. On top of this, measuring the costs and benefits of college conclusively is indeed complicated and requires some guesswork. And there are some important caveats to the rosy picture. Here are the main themes from the skeptics.

High returns apply to people who graduate, but almost half of people who attend college do not graduate. This is true – and it implies a big opportunity for parents to shepherd their kids into colleges with high graduation rates and then continue supporting them through graduation. However, even people who attend college and don’t earn a degree experience substantial earnings gains that typically exceed their costs.

High returns mask enormous variation across colleges and fields of study – and some college degrees don’t benefit people at all. This is true and it creates a big opportunity for parents to guide kids toward good colleges and good majors. And while some people view this point as a kind of “gotcha” for college, it’s true of most averages. Over the course of decades the stock market performs well, but many individual stocks do terribly and many do great. With the stock market, the right answer for most people is to avoid trying to pick winners and invest in the overall market. With colleges, you have to pick one – but it’s far easier to pick winning colleges and majors than it is to pick winning stocks.

People who attend college would have done better anyway. People who attend college do start out with more skills, but the best studies find big causal impacts of college on earnings, to an extent that is remarkably consistent with the magnitude of the college earnings premium. Some skeptics talk about this problem as if there are a bunch of studies that show colleges just recruit smart people predestined for good careers and add no value, but such studies do not exist.

College used to be a great bet, but things have changed. The earnings advantage of college graduates has remained enormous over the last decade. Meanwhile over the last 20 years real out of pocket costs of college grew by a few thousand dollars but then stabilized and recently started to fall. College remains a great bet.

There is one scary paper that has gotten some high-profile attention. It claims that, despite the high college earnings premium, the college wealth premium has disappeared for recent cohorts born in the 1980s, allegedly due to higher costs. Multiple folks have pointed out this paper makes some some big mistakes and is almost surely raising a false alarm. People born in the 1980s were still too young to see the expected wealth benefits of college in the researchers’ data. Earlier generations also exhibited small college wealth premiums at similar ages.2

AI will replace most college-educated workers. For now we still have no idea. I’ve highlighted reasons why AI might wind up increasing the value of a college degree:

In fact, I’ll bet that over the next 30 years AI will favor higher-skilled workers, and thereby tend to make inequality worse. … Yes AI can write papers, it can code, it can analyze data. But that just makes people with good ideas for papers, software, and data projects – and people with the ability to evaluate and build on AI’s imperfect work – that much more productive. People with these skills are scarce. Steve Jobs described the computer as a “bicycle for the mind.” To me AI feels like a race car for the mind – not a replacement for the mind.

It’s also worth mentioning that some anti-college rhetoric is just hot air. All the critics have college degrees, and if any of them feel confident their own kids and grandkids should not attend college they haven’t stated that in their writing. New America’s “Varying Degrees” annual survey finds Americans are less skeptical toward the importance of college for their own family members than they are toward college for the broader public.

So college is indeed a great investment. In part 2 of this post, we’ll see how parents can help their kids tap into that investment and make the most of it. For families that aren’t rich and aren’t bona fide experts in our screwball college system, we don’t make it easy.

I know this is a whimsical calculation but I still find it useful. CSU San Marcos enrolls 17,000 students, 58% of each cohort graduate in an average of 5 years. Each degree creates ~$300k of new wealth (Barrow & Malamud 2015, Zimmerman 2014). These numbers imply each year CSUSM creates $590m additional income with its ~$230m budget. A company generating $360 million per year in stable, low-risk “profit” might have a valuation in the range of $5 billion using a 5-10% discount rate. This is just a quantitative way to say that colleges churn out a lot of people with far better careers than they would have experienced otherwise and that adds up to a lot of money compared to colleges’ operational expenditures.