What We Learn From Birth Order

First-born kids do better and that's ok.

My wife and I have two kids. The older boy loves the Pixar Cars franchise. As a result, the younger girl also loves the Pixar Cars franchise. She says “TV” and “Cars” (sometimes “Cars 1”) all the time. She’s 1.5 years old. When our son was that age he watched a lot less TV. With two kids we’ve struggled to summon the time and energy it takes to avoid more screen time. Admiring our little girl on the couch as she stares into the TV fills us with ambivalence.

So the other day blogger Caroline Chambers caught my eye when she wrote: “One of my core philosophies … is the idea of raising your first kid like it’s your third kid.” She describes how she dialed down her intensive parenting tendencies with her later-born kids because she didn’t have enough time anymore, and as a result she finds the whole parenting thing “so, so, so much more fun.”

Is this a good philosophy? It reminded me of the “good enough parenting” idea that different people cite to justify both more and (typically) less public investment in kids. I’ve argued against this view because the best evidence suggests a lot of hard, expensive investments in kids do have value even if we can’t ask individual parents to do them on their own, and we shouldn’t judge ourselves or others for failing to do them.

But Chambers’ philosophy still appealed to me! Along with more TV, our 2nd-born kid has gotten less one-on-one reading, conversation, and play time with her parents. Every parent I know with more than one kid reports the same thing. It would be great if these differences didn’t matter, or if the benefits of having an older sibling or more experienced parents mattered more than the loss of so much focused parental attention.

Unfortunately, there’s good research on this and it’s not all that reassuring.

Compared to earlier-born kids in the same families, later-born kids tend to get less education, score worse on tests of cognitive skill, receive lower ratings on assessments of social and emotional skills, earn less money in their careers, are less likely to wind up in jobs associated with leadership skills, and are more likely to get involved in substance abuse and crime. It’s not a great picture.

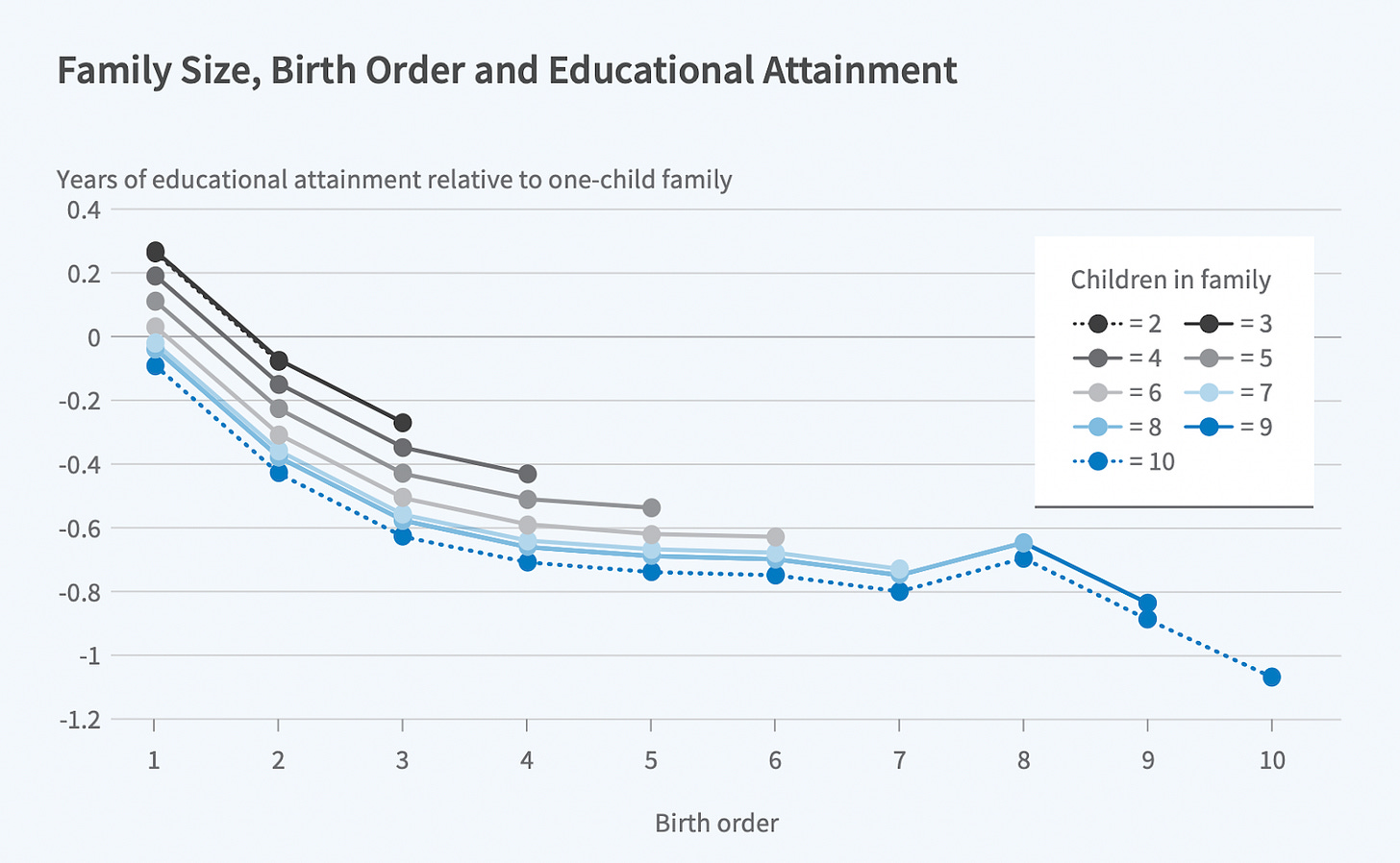

Here’s a figure from the leading researcher on this issue, economist Sandra Black, showing kids’ educational attainment by birth order and family size using data from Norway. The pattern is striking – in families of all sizes, later-born kids get significantly less education than earlier-born kids. Researchers have found this pattern across many countries so it’s not an artifact of any one society. It’s deep.

How big are these impacts? The best estimates suggest that Chambers’ “third-kid parenting” philosophy (which is obviously well-meaning and really might be wise when taken less literally than I’m doing here) would lower all kids’ future earnings by about 5% (2-3% per rung of birth order). That’s not apocalyptic, but it’s also not trivial. It’s on the order of $100,000 in lifetime income. If we think about this like a tax, it’s much larger than the full Medicare tax rate of 2.9%. (As always I don’t believe income is a good measure of human success, I just use it as a rough barometer for impacts on personal freedom and quality of life.)

Why does this happen? The short answer is “good enough parenting.”

Economist Joseph Price looked at data on parental time use. He found “in two-child families, the first-born child receives about 20 more minutes of quality father-time and 25 more minutes of quality mother-time each day at each age than the second-born child does at the same age.” This adds up to thousands of hours over the course of childhood, and we see it reflected in other studies finding later-born kids watch more TV and spend less time discussing homework with their parents. Why do parents invest less in later-born kids? Price finds it’s mostly because parents give undivided attention to firstborns, but then divide attention equally among all kids going forward rather than trying to give later-born kids their “fair share” of undivided attention.1

Does this mean parents are making a mistake? I don’t think so. Knowing these facts might help some parents avoid leaning too hard into “good enough parenting” under a false premise that it won’t matter. But parents can’t just neglect first-born kids once later-born kids arrive in the name of fairness. I don’t think birth order impacts are important because they are a call to arms that we should be giving all our kids perfectly equal opportunities.

Rather, birth order impacts are important because they provide a familiar window onto the importance of child development more generally. Apparently, there is no “good enough” in sight. And if subtle opportunity gaps between earlier- and later-born kids in the same freaking family matter this much, imagine how much enormous opportunity gaps across more and less advantaged families must matter! These findings reinforce more direct evidence confirming the value of high-quality child care, schools, after school and summer activities, and all the other learning environments we the public determine for kids through legislation or its absence.

Still, birth order impacts might stress you out personally as a parent. It jolted me to realize our daughter may well pay a price for that extra TV time. How hard should we try to do something about this? Here I’ve used a different rule of thumb than the “third-kid parenting” approach proposed by Chambers. I think of it as a “categorical imperative for parents”:

Don’t make sacrifices for your kids if you’d be sad to see them make those same sacrifices as adults for their kids.

Someday my kids might have their own kids – maybe more than one. If that happens, do I want to set them up with an expectation that they should strive mightily toward birth order neutrality among their kids? No. Raising multiple kids unequally is already hard enough. I’d much rather my grown kids protect their relationships, health, careers, and joie de vivre against all the strains of parenthood, and save any spare energy to solve bigger problems.

Reflecting on that helps to counterbalance the drag of knowing my younger daughter won’t ever get as many hours sitting in our laps reading I Am A Bunny as her older brother, despite being an equally mesmerizing, curious, pear-shaped little space alien. And that counterbalance in turn makes it a little easier to sit back and enjoy the look on her face as she blisses out on the couch watching too much TV.

A little easier. Honestly, I still really wish she were building Lego dreamworlds or reading with us instead. I’m not gonna sell you too hard on my desperate little self-help heuristics :-).

Price also documents a second less obvious reason why younger kids get less time with parents. It turns out that parents dial down their overall time engaging in high-quality parenting activities as their kids get older, especially as a function of their oldest child’s age. This means younger kids get equal shares of a smaller number of parenting hours compared to their older siblings. It’s as if that first kid in particular speeds up the aging process for parents and they soon become too exhausted to put in all the hours they did at first.

I think this does show there is a pretty low marginal return to the "last hour" spent with a child. It seems like halving the amount of time you spend (by adding another child and splitting your time evenly) roughly decreases educational attainment by 0.2 years , which is kind of underwhelming.

Super interesting post. Thanks for writing this and sharing.

As a psychologist I can’t quite contain my need to clarify the author’s relative misuse of “good enough parenting” (though I completely understand that the author is referring to it in the way that parents following this mindset are colloquially using it - AND who are also misunderstanding the original meaning). It absolutely does not mean more relaxed parenting in terms of providing less attention or time or some arbitrary measurement of ’good enough.’ It also doesn’t mean less hypervigilance or less effort. What it means is accepting that inevitably we will all make tons of mistakes as parents. But given the combination of a genuine best effort and the opportunity to repair any harms done that sting longer than the moment, the parenting will be ultimately be good enough. The term comes from a psychoanalyst named DW Winnicott. And it’s a beautiful perspective that I think when held well alleviates some of the guilt and worry parents can feel about what they might have done that was more negatively impactful then they anticipated or could mitigate, while also setting up the mindset that you can still repair wounds. Winnicott also argues that those very same ‘harms’ when repaired between parent and child are tremendous learning opportunities that are ultimately more beneficial than having done it perfectly in the first place.